Talk to any seasoned veterinarian and they’ll be the first to tell you that while technology and diagnostic imaging have made significant leaps forward in the last decade, their best and most effective tools are their eyes, ears and hands.

With Improved Diagnostics and New, Advanced Treatments and Rehabilitation Techniques, Disease States and Injuries Affecting The Equine Cervical Spine are at The Forefront of Veterinary Medicine

If we compare the horse and human side-by-side, we learn that we’re not so different from one another. Take the neck, for instance, more properly known as the cervical spine region. We humans quickly ascertain the importance of the cervical spine and surrounding musculature when our necks are tight, stiff or painful. We find it difficult to move normally or comfortably, let alone perform as athletes. The same holds true for our four-legged counterparts, with the equine cervical spine region emerging in recent years out of a cloud of unknowns into the daylight of clarity and purposeful action within equine veterinary medicine. Here, three experts in the field — Melinda “Mindy” Story, DVM, PhD, DACVS, DACVSMR, cVMA, cIVCA; Will French, DVM, cVMA, cIVCA, ISELP; Kyla Ortved, DVM, PhD, DACVS, DACVSMR — lend their knowledge and hands-on learning to share the latest research and clinical advancements related to the equine cervical spine region.

Physical Exam and Diagnostic Imaging

Understanding the Cervical Spine Region

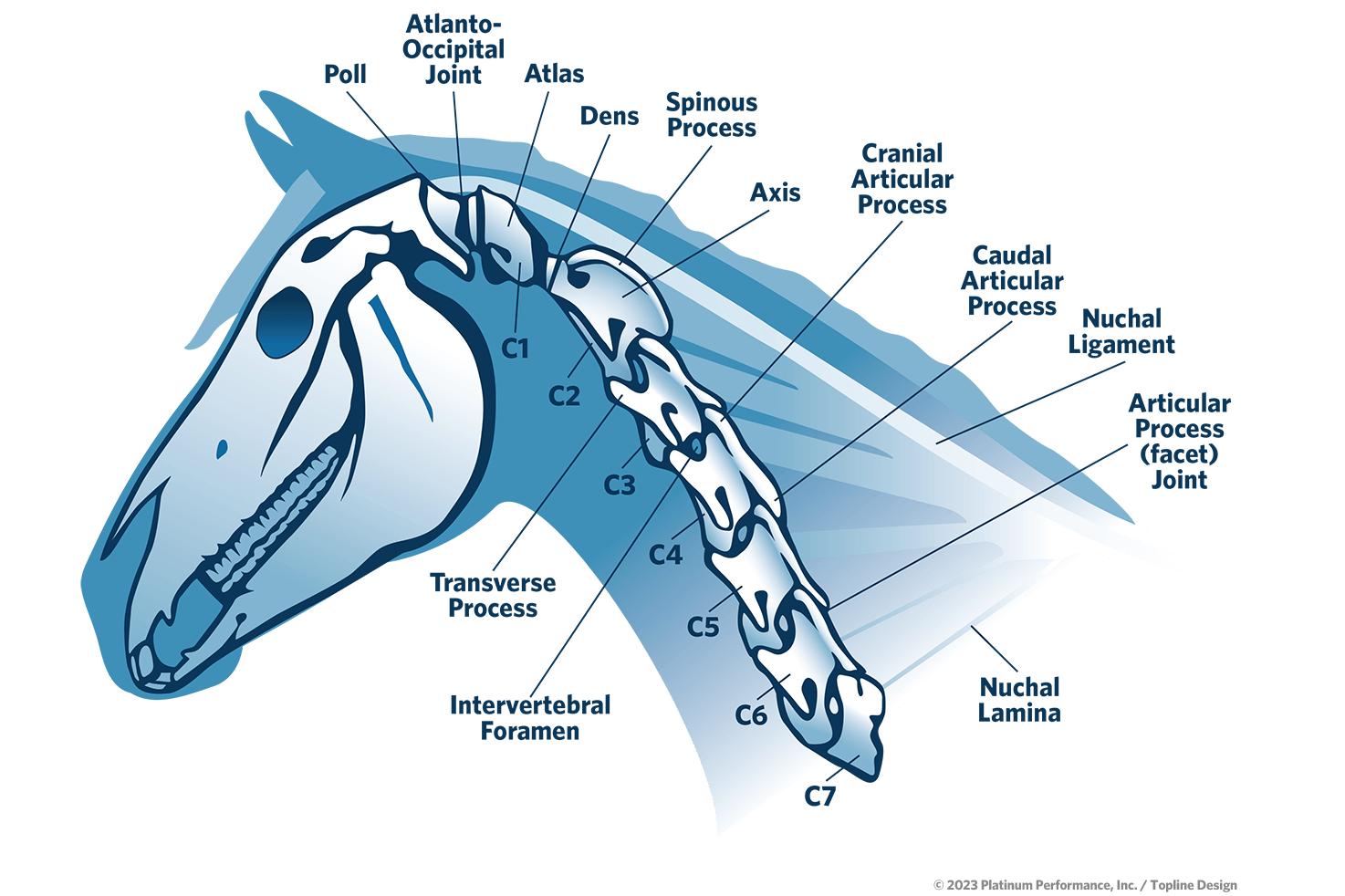

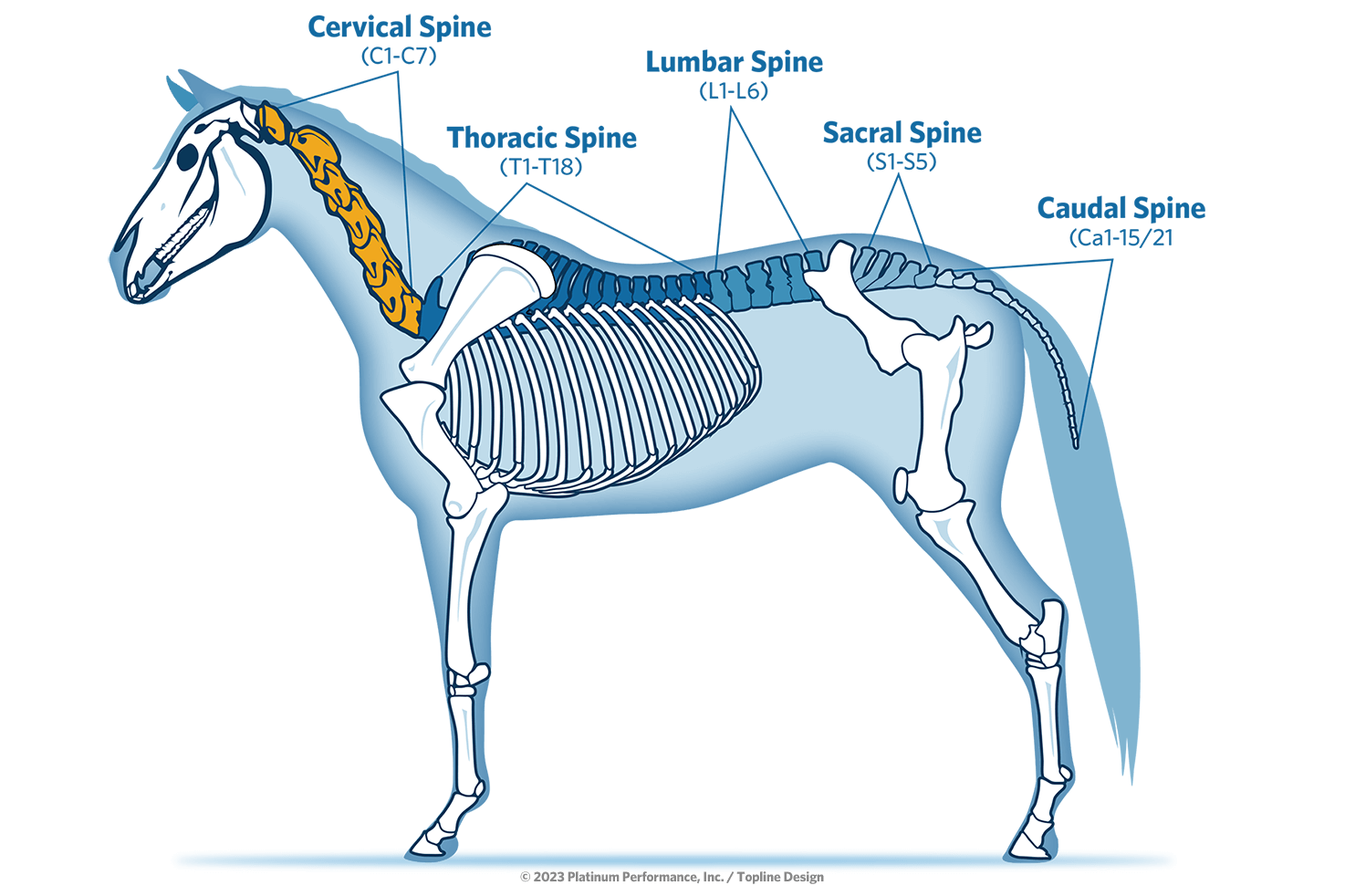

At a glance, equine cervical anatomy runs from the ears to the horse’s withers, encompassing the cranial cervical vertebrae C1 through C7 (with some disease-processes of the region also encompassing the cranial thoracic vertebrae of T1 to T3). While the first thing that comes to mind is the bony column, which surrounds and protects the spinal cord, the intervertebral discs and articular process joints; it’s important to note that the cervical region also incorporates other supporting soft tissues — including the nuchal ligament (a large, elastic structure in the dorsal cervical region that helps support the head and neck), muscles and nerves. “All of this is so critical to making the cervical region function properly,” says Dr. Mindy Story, a widely-respected equine veterinarian with board certifications in equine surgery and equine sports medicine and rehabilitation, along with certifications in equine chiropractic care and acupuncture. She’s also a practicing clinician at Colorado State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences in Fort Collins. “We can’t just look at one structure; that can lead us down a rabbit hole that may or may not prove to be the right direction. The cranial cervical region up in the poll area (behind or between the ears) can have a whole different list of problems and complications that we need to focus on versus the lower neck and down into the cranial thoracic region.” This complex collection of structures is what makes the neck so fascinating and frustrating to sports medicine practitioners. “If a horse is stiff or not bending their neck correctly, it could be any one of those factors or a combination of all of them,” highlights Dr. Will French of the puzzle that is the equine neck. The fifth generation Colorado native, who grew up in Fort Collins, is an equine veterinarian, ISELP-certified practitioner and partner at the famed Littleton Equine Medical Center in Colorado, 15 miles south of Denver. “As veterinarians we have to remember that there’s often more to what’s going on than what we see on the screen in front of us,” he cautions.

Cervical Spine Region

When examined in detail, the cervical spine region is complex, involving muscles, nerves, bones, joints and the spinal cord.

Where is the Cervical Spine?

The equine neck (cervical spine region) reaches from the Atlanto-Occipital Joint (poll) on through the cervical vertebrae of C1-C7 and may sometimes incorporate disease and injury related to T1-T3 of the thoracic spine as well.

Disease Categories Associated with the Area

Aside from injuries that can affect the cervical spine region, three main disease categories are commonly considered, including structural disease such as type I and type II cervical vertebral stenotic myelopathy (CVSM), osteoarthritis of the articular process joints and intervertebral disc disease; infectious diseases like EPM (equine protozoal myeloencephalitis that affects the equine central nervous system) and Lyme neuroborreliosis; and neurodegenerative diseases such as equine degenerative myeloencephalopathy (EDM) and equine neuroaxonal dystrophy (eNAD), which can affect the spinal cord and the brain leading to neurological deficits and behavioral changes.

The Visual, Physical and Ridden Exam

Talk to any seasoned veterinarian and they’ll be the first to tell you that while technology and diagnostic imaging have made significant leaps forward in the last decade, their best and most effective tools are their eyes, ears and hands. “I start with a visual exam before I ever put my hands on the horse,” says Dr. French of his process. “I’m looking at the horse and asking myself, ‘What is their musculature? Are they underdeveloped? Do they have atrophy? Are they symmetric from side to side?’ The ventral musculature may be overdeveloped, and they may be carrying themselves in an inverted frame. Or there may be a deformation at the poll around the nuchal ligament or maybe even the nuchal bursa. If you just take a minute to look, before you even put your hands on the horse, that’s a crucial place to start.” Among the information gleaned from a good visual exam are signs of muscle atrophy and asymmetry from side to side and front to back. “Sometimes we have these big, massively muscled horses from their shoulders to their tail,” observes Dr. Story. “When we look at their neck there’s nothing there. That’s not how a horse is meant to be; they should have symmetric muscling everywhere.” Muscle atrophy (or underdevelopment of the neck) is one of the best clinical signs to indicate cervical disease and dysfunction in the horse, she says, adding: “Above radiographs (X-ray studies), above all other things, muscle function and size are some of our best indicators.”

While a visual exam lays the foundation, a framework of understanding builds with the physical exam and, past that, the neurologic exam. “After I’ve spoken to the owner then stood back and watched them, then it’s time to get my hands on the horse,” she says of her next step. “I need that horse’s nervous system to talk to my nervous system, and the best way to do that is through my fingers.” Honing a veterinarian’s hands to really feel a horse’s tissue and simultaneously interpret what they’re feeling is an expertise that heightens the diagnostic process. “I’m asking myself, ‘How does the skin move in relationship to the muscle?’ ” Dr. Story says. The skin should be soft, pliable and movable across the muscles, with the muscles having a soft tone. “I’m looking for skin texture and tone and fascia associated with the muscle and any reactivity,” she explains. When it comes to palpation, an easy touch is a more successful one. “Start light,” Dr. French affirms. “If we as veterinarians go in hard at the beginning in hopes of finding that sore spot, we’re going to miss so much of what might actually be there.”

As part of the initial exam phase, a neurologic exam is often incorporated for cases with certain symptomology that includes even subtle hints of neurodegeneration that can leave a horse unsafe to ride. This will include the veterinarian performing a standard set of neurologic tests that, according to the American Association of Equine Practitioners, an organization that includes 9,300 veterinarians in 61 countries, can include four sections: evaluation of mental status; a cranial nerve examination; spinal reflexes and a muscle evaluation (performed on a standing horse); and a gait and postural examination (performed on a moving horse).

Beyond the visual, physical and neurologic exam is a final step in the diagnostic process prior to bringing in imaging technology. A gait evaluation includes watching the horse in hand, while lunging and in a ridden exam, allowing the veterinarian to observe vital clues while the horse is under saddle and in exercise, ideally performing its native discipline. “(This), particularly for the neck and spine, can be crucial and provide a lot of information,” confirms Dr. French. While the observations help get to the root of the problem, he’s quick to raise caution in terms of the safety associated with climbing aboard a horse with a potential issue related to the cervical region. “Any time we ask someone to get on a horse, there’s risk,” he says with gravity. “It’s something that we need to think about. Even if it’s a professional that’s getting on that horse.”

Worth mentioning is the pre-purchase exam and how the neck factors in. “It’s a tricky area no doubt,” confirms Dr. French. “It’s difficult for me to look at radiographs on a pre-purchase exam and not have my hands on the horse. I like to know what my fingers are telling me. For me to just provide an opinion on some radiographs where a horse has some mildly-enlarged facets can be difficult.” In addition to performing a physical exam, Dr. French typically recommends neck radiographs when performing a pre-purchase. He’s a firm believer in honest conversations and clear communication with prospective horse owners standing in front of him. “I have a conversation with nearly every buyer. The pre-purchase is not necessarily a pass or fail situation for me. It’s more about risk management,” he says.

While diagnostic technology remains immeasurably important, a veterinarian relies on his or her senses to succeed in these cases. “We go through veterinary school and pay a lot of money for our eyes and our hands,” says Dr. Story. “Radiographs, MRIs (magnetic resonance imaging), CTs (computed tomography) and ultrasounds are absolutely helpful, but without our eyes and hands, nothing else actually matters.”

Diagnostic Imaging

Imaging is one of the bigger weapons in a veterinarian’s diagnostic arsenal when it comes to the cervical region. Numerous imaging modalities can come into play, each with its own benefits and drawbacks. The use of a diagnostics stack, where more than one type of imaging is performed, may be more effective in gaining well-rounded perspective.

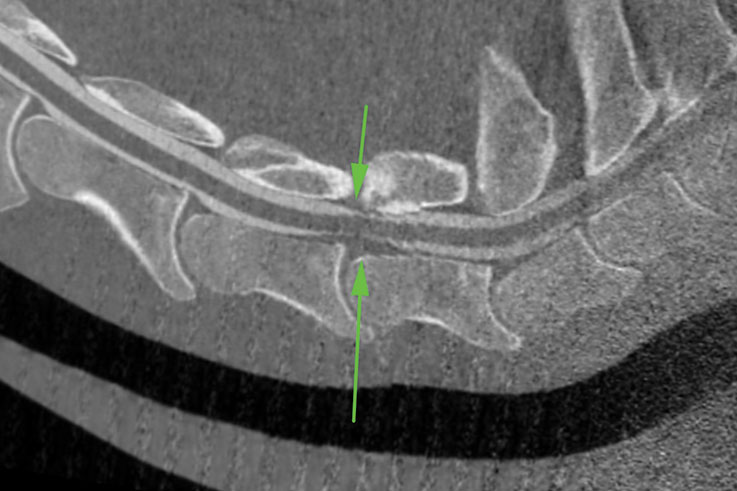

This CT myelogram shows compression of a horse’s spinal cord at the C6-7 articulation, seen as loss of contrast from both a ruptured disc (lower arrow) and from an enlarged articular process (upper arrow). Other views also revealed stenosis (narrowing) of the intervertebral foramen at the C6-7 articulation.

First and foremost, most veterinarians begin with radiographs as the frontline diagnostic standard when searching for disease or injury of the cervical region. Radiographs, however, follow the adage: “Anything worth doing is worth doing right.” Or, put another way: A bad radiograph can hinder the diagnostic process, but a good, complete radiographic study can point a practitioner toward a clearer next step. While 2D radiographs have limitations, they are extremely useful when captured correctly. The addition of oblique angles is of some debate in veterinary medicine, with some practitioners believing in their added value, while others adamantly oppose capturing these added angles due to high complexity and additional radiation for the veterinarian and staff. “I’ve seen both ends of the spectrum,” says Dr. Story of the controversy. “Obliques are really helpful, but we’re thoughtful about them. Taking 12-16 views of every neck just isn’t safe.” She emphasizes that proper technique is key when it comes to capturing quality oblique-angle views: “As veterinarians we need to make sure we know exactly what we’re looking for. It takes time and talent to get to the place where you can consistently capture good quality radiographs.” While radiographs are an important first step, ultrasounds are another widely used tool. “It can really add a lot to the exam,” she says. “If I’m worried about a neck, we’re going to get radiographs and ultrasound. They complement each other very well and there are reasons and indications for both modalities,” she adds. In full agreement, Dr. French also uses that combination in his diagnostic process. “I know this is expensive for the owner, but it’s amazing how sometimes a facet (articular process joint) can look pretty bad on a radiograph, then on that corresponding ultrasound, it looks pretty good and vice versa. They provide complementary information.” In contrast, ultrasound offers the ability to evaluate the capsule for thickening, the presence of increased effusion and a good view of the muscles.

While radiographs and ultrasound may be the one-two combination that most practitioners reach for after their visual, physical and gait examinations, computed tomography, or CT, is a more advanced imaging choice for the cervical region. “Some people question MRI versus CT,” Dr. Story says, addressing a common question. “We can’t successfully MRI a horse’s neck. The technology just isn’t there.” While veterinary medicine is still in a growth phase with CT, that uses specialized X-ray equipment to produce incredibly clear 3D cross-sectional images, access to this technology is expanding and the profession is gaining new and valuable information each day. “The neck is a 3D structure, so CT changes everything,” Dr. Story insists. Not all CTs are created equal, and access to the right equipment can be a challenge at the moment. The technology is rapidly becoming more streamlined and accessible, however, with more referral hospitals gaining access to CTs and thus offering this valuable imaging to more patients. “We are going to gain so much information over the next five to 10 years. We’ll have a whole different understanding of the entire cervical spine region,” she says.

Treatments and Rehabilitation

Common Disease States and Injuries of the Cervical Spine Region

At its core, a horse’s neck — cervical spine region — is an incredibly complex anatomical structure with numerous areas where disease and injury can occur. “If you think about our own necks as humans, and how complex they are — muscle, nerve, bone, joint, spinal cord — there’s a lot going on there,” says Dr. Ortved. The associate professor of large animal surgery at the University of Pennsylvania, in Kennett Square, is well-practiced in diagnostics and treatment surrounding the cervical spine region as an equine veterinarian with twin board certifications in equine surgery and equine sports medicine and rehabilitation. She practices and teaches at the university’s New Bolton Center, where she oversees the Ortved Orthopedic Regenerative Medicine Laboratory. The lab is focused on understanding the physiological processes of post-traumatic osteoarthritis (PTOA) and developing gene and cellbased therapies to help regenerate cartilage and prevent the development of PTOA following joint injury.

There are several diseases that can affect the cervical spine. We often consider three main groups of disease including structural disease, which would include such things as type I and type II cervical vertebral stenotic myelopathy (CVSM), osteoarthritis of the articular process joints and intervertebral disc disease; infectious diseases, which would be things like EPM (equine protozoal myeloencephalitis that affects the equine central nervous system) and Lyme neuroborreliosis, which is uncommon but can also be very problematic; and neurodegenerative diseases such as equine degenerative myeloencephalopathy (EDM) and equine neuroaxonal dystrophy (eNAD), which can affect the spinal cord and the brain leading to neurological deficits and behavioral changes.

“In addition to the bones and joints, the soft tissues are critically important,” adds Dr. Story. “These are the discs, ligaments and muscles in the region, and they definitely play a role. Every structure must be thought through and evaluated, and we have to decide if it’s part of the pathology. That pathology is oftentimes multifactorial, and if we think about every structure and every tissue type, when we make our plan, we’re more successful in the end.”

With advancing knowledge and improved imaging, the ability to pinpoint disease processes and injuries in the neck has improved dramatically in the past 10 years. Coupled with riders more finely attuned to the cervical region, practitioners admit that equine medicine has come a long way. Said Penn Vet’s Dr. Ortved: “Some of the clinical signs we see are so subtle, and an owner will come to you and say, ‘My horse just started doing this recently.’ It’ll be a subtle sign, but it's important and valuable. Riders contribute a lot to this process.” While riders are closely connected to the nuances of their mount’s behavior and movement, do we see a higher percentage of performance athletes displaying signs of disease in the cervical region, or are discipline and performance level not a factor? “This doesn’t discriminate, all horses can be affected,” says Dr. Ortved, whose career has focused on equine surgery, with a special focus on orthopedic surgery, including arthroscopy, tenoscopy and fracture repair. “However, we do see CVSM and osteoarthritis of the articular process joints quite commonly in high-level athletes though, especially in their caudal cervical spine (C5-C7). Those high performers may be at increased risk of lower neck pathology or osteoarthritis because they’re elite athletes and they place high demands on their bodies including their necks. In addition, their jobs demand a high level of fitness and coordination, so subtle deficits may be more obvious.”

Dr. Alicia Yocom, of Bayhill Equine, palpates a horse’s neck during an exam.

With advancing knowledge and improved imaging, the ability to pinpoint disease processes and injuries in the neck has improved dramatically in the past 10 years.

“If you think about our own necks as humans, and how complex they are — muscle, nerve, bone, joint, spinal cord — there’s a lot going on there.”

— Dr. Kyla Ortved, University of Pennsylvania

Symptomology

Like humans, no two horses are alike in how they present with symptoms of disease, with the neck being a prime example. Injuries or disease of the cervical spine region will cause outward signs that range from subtle behavioral changes and mildly impaired movement to more dramatic symptoms of severe stiffness, inability to perform, violent behavior, severe ataxia and more. “The signs can be so subtle that we really have to pay close attention and listen carefully to what the horse is trying to tell us,” observes Dr. Story. “There are those middle-ground cases where they’re presenting as stiffer and more arthritic. They may not be able to fully turn their head properly or we may be seeing a forelimb lameness that doesn’t localize to the limb, or perhaps the horse is unable to lift through their thorax to collect in dressage. They can present in nearly any way.”

Whatever the patient’s symptoms, examining the horse globally as a collection of interrelated systems is a keystone to success. “Whether it’s a front limb lameness, a hind limb lameness or a simple case of poor performance or weight loss, every body system, every body part has to be considered in order to do our best medicine,” Dr. Story insists.

Ascertaining a Treatment Protocol

Dr. Jen Williams, of Steinbeck Peninsula Equine, performs acupuncture on a horse.

After bringing together the visual, physical and gait examinations, along with diagnostic imaging and an assessment of symptomology, it’s time to establish a treatment protocol that considers case specifics. Treatment might include intra-articular therapies, mobilization techniques and some pain modification, including acupuncture or other modalities like laser or PEMF (pulsed electromagnetic therapy), etc.

After bringing together the visual, physical and gait examinations, along with diagnostic imaging and an assessment of symptomology, it’s time to establish a treatment protocol that considers case specifics. “Our treatment plan is obviously very dependent on the diagnosis, and there’s a wide variety of diagnoses that we see,” says Dr. Ortved. One of the most common conditions is osteoarthritis, or OA, of the articular process joints. “If I have a horse with arthritis of an articular process joint, I start with the basic things just like I would any other joint,” Dr. Story says of her approach. “I have different tiers of treatment that I think about. In some horses that are showing mild pain and more stiffness secondary to their OA, I may start with some mobilization techniques and some pain modification with things like acupuncture, or include other modalities like laser, PEMF (pulsed electromagnetic therapy), etc. If those are unsuccessful, or only minimally successful for a short period of time, then I’ll go to my second layer of treatment in addition to including my level-one modalities; and that second tier would include the intra-articular therapies, of which there are quite a few options and can include biologics and steroids. This is also an area where nutrition plays a huge role. I like to keep them fit, healthy and strong from the inside out. It’s really a whole-horse approach.”

Some horses with OA of the articular process joints will have stenosis of the intervertebral foramen, the opening between every two vertebrae where the nerve roots exit the spinal cord, “There should be a nice wide opening, but instead we see a lot of horses with bony growth and soft tissue compressing the nerve,” Dr. Ortved explains. These horses may benefit from injections around the nerves, physical therapy, and possibly newer surgical treatments that are being developed.

The treatment plan would be based on the horse’s individual diagnosis and where the animal falls on the spectrum within the veterinarian’s assessment. “Whatever their diagnosis, it is critically important to take a whole-horse approach,” Dr. Story emphasizes. “We have to not only consider the metabolic state from the perspective of what we put into the joint — a biologic versus a steroid — but we also need to ask ‘What do we need to address with that horse systemically to make them healthier and to decrease the inflammation in their body?’ I can put something in their joint all day long, but until I manage the body as a whole, any other treatment is not going to be as effective. That’s again where nutrition comes in, as part of that longterm strategy. It’s also where the rehabilitation comes in. When I have any case with a problem, my goals are to decrease pain, deal with the structure if we have a structural problem, improve mobility and strength, and manage that through a whole-systems approach.”

The Value of Rehabilitation

The goal of a rehabilitation program is to restore mobilization, comfortable movement and hopefully return the horse to work with the ability to readily and happily perform their job without pain. “Mobilization is really important,” confirms Dr. Story. She is certified in animal chiropractic, and while that modality can be wildly beneficial, she’s quick to caution that it should be used by veterinarians licensed to perform chiropractic care, and its use should be conservative and based on the specifics of individual cases. “I feel very strongly as a person who does chiropractic that you have to be very conservative. While mobilization is important, and chiropractic is oftentimes beneficial, it can also do harm when used in cases where it shouldn’t be.” Dr. Story cautions that chiropractic treatment should not be used if a horse is reacting in an unexpected way, if the practitioner feels like there’s more happening beneath the surface and if there’s any neurologic involvement. “I don’t want to make the horse more unstable or worse in their ataxia,” she says of her careful use of chiropractic. She and her team will perform imaging, most often including a combination of radiographs and possibly a CT, then ensure that if they move forward with chiropractic, the horse is actively engaged in the mobilization and in a conscious state. “We as practitioners need to be thoughtful and conscientious about what we ask those tissues to do,” she reiterates. “If it doesn’t feel right, we need to gather more information. There may be an old fracture that nobody knew about, or the horse may have had surgical cervical stabilization that we’re not aware of. Owners don’t always know the entire history on that horse.”

While chiropractic care can assist in mobilization with cervical spine region cases, strengthening key supporting and stabilizing musculature — especially muscles comprising the equine core — can also make a tremendous and long-lasting impact. “These muscles support and protect potentially fragile places like joints, discs, etc.” explains Dr. Ortved. “There are exercises that are specifically intended to strengthen the core. We can get very specific, very directed and very targeted.” An example can be seen in the multifidus muscles along the spine, which greatly impact a horse’s core strength and also stabilization. “If that multifidus, which spans multiple segments, isn’t doing its job, then every segment at every level is not functioning properly. Those muscles aren’t firing properly,” Dr. Story explains “If the multifidus has atrophied at all, then every joint along that level takes the hit instead of the muscle. Those joints aren’t intended to be put under that degree of strain, that can cause those structures to fail. The joint capsules and the cartilage are at an increased risk of injury, and the disc is potentially going to become abnormal and dysfunctional,” she says. “Over time, that’s when we may run into problems.”

From a rehabilitation perspective, the mission of supporting proper mobility and function incorporates a multipronged approach that includes a thoughtfully-designed exercise program and supportive nutrition protocol. “It’s important that when I’m looking at a horse with axial skeletal disease, I’m aggressively supporting the nervous system — the nerves and nerve function. The articular process joints are big joints with many pain fibers that we need to support. Drs. Story, Ortved, French and their peers closely watch advancements happening around the equine gut microbiome, with established links between that vital system and the brain, heart, lung and reproductive systems now known. “Again, it’s about evaluating and supporting the whole horse, paying attention to the microbiome,” says Dr. Story.

While a diagnosis related to the cervical spine region may incite fear in an owner, the message here is not to lose hope. Significant steps forward have been made in how veterinarians identify, treat and rehabilitate diseases and injuries of the neck. With more concrete and time-tested rehabilitation and nutrition protocols, these patients often return to work in an ideal condition able to manage their diagnosis and still comfortably perform their job.

The Equine Spine Initiative

Advancements in cervical spine treatment are the result of significant effort, focus and a team-based approach within equine veterinary medicine. A recently formed group of specialist veterinarians, known as the Equine Spine Initiative, or ESI, is raising the bar in terms of research, establishment of solid treatment protocols and the creation of detailed rehabilitation recommendations. Dr. Story and several colleagues have been a driving force behind this group, and their lofty goals. “The ESI developed out of a need to try to bring information to more veterinarians, clients and owners,” she explains. “There are those of us that focus in this area, and it’s a huge part of our daily jobs. The group has pathologists, radiologists, neurologists, sports medicine specialists, rehabilitation specialists, surgeons and people who have a little extra passion for the cervical region.” The team assembles several times a year and communicates regularly on their continued work and shared mission. “This group is about bringing everybody together who has thoughts around this area, so that we can develop protocols while still respecting an individualized approach to each horse,” she says.

The group has an extraordinary lineup of influential veterinarians, all coming together to benefit the horse. They’re scientists, detectives and problem solvers whose sights are set on the cervical spine region, with hopes of unlocking the unknowns of this complex structure. “I feel very fortunate to be a part of it,” Dr. Story says.

“We all have something to learn every day from the horse. We have to let them be creative in how they tell us those things. We can’t stop looking until we’ve sorted it out, so that they can ultimately be happy and perform at their best.”

— Dr. Will French, Littleton Equine Medical Center

Where We’re Headed

While much progress to better understand the cervical spine region has occurred, there’s still more to do. “The neck is becoming something that people are much more in tune with,” says Dr. Ortved. To her, and Drs. Story and French, they hope to see more colleagues readily considering the neck when a horse’s behavior and confounding lamenesses call for it. “Our ability to diagnose is so much better than it used to be,” Dr. Ortved adds. “As a result of that progress, we are much better able to treat things appropriately and get a horse back to where it wants to be.”

While the neck is complex, Dr. Story insists that owners should observe and respect their gut impressions: “Listen to your horse, watch them and don’t doubt yourself if you feel like something is off. As a veterinarian, there’s so much to hear from an owner if I stop and really listen.” It’s then that a veterinarian can take a step-by-step diagnostic approach and when in doubt — expand his or her diagnostic team. “We’re going to knock off the checkmarks of what we know, which will lead us to the action we need to take,” she says. “There are some of us who focus on this every day. I’d encourage our colleagues to reach out; we’re happy to be part of that team. My best example is that I’ve literally never floated my horses’ teeth — ever. I’m not a dentist. I have somebody come in and do that. I don’t need to be that person. Along the same lines, I would never go out and do repro ultrasounds. That’s not what I do. Thankfully, we are blessed to be in a profession where we can have veterinary specialists to lean on. The more we appreciate that team approach, the better off we and our patients will be.”

Expertise offered by Drs. Story, Ortved and French, and the Equine Spine Initiative, delivers increased hope to owners and their animals for longer, healthier and more productive lives. “We all have something to learn every day from the horse,” Dr. French says. “We have to let them be creative in how they tell us those things. We can’t stop looking until we’ve sorted it out, so that they can ultimately be happy and perform at their best.”

The Platinum Podcast

Investigation Spine

World class equine veterinarians and experts in the equine cervical spine region, Drs. Mindy Story, Kyla Ortved and Will French, offer their insights on symptomology, the physical exam, diagnostic imaging, treatment modalities and the advancement of rehabilitation. Join us on a deep dive into the cervical spine and why this region of the horse’s anatomy is crucial to optimal performance and longevity.

Listen Now