Medical Advancements Now Allow Horses to Survive and Return to Work

Innovative surgical techniques, advanced diagnostic technology, improved hardware and science-backed rehab allow for maximum patient comfort and a successful return to work.

Equine fractures are, thankfully, quite rare in comparison to other injuries horses may face in their lifetimes. Accidents do occur however, and the practice of fracture repair and rehabilitation has experienced tremendous progress with vastly improved patient outcomes. The days of immediate euthanasia for certain broken bones have been replaced by innovative surgical techniques, advanced diagnostic technology, improved hardware and science-backed rehab protocols that allow for maximum patient comfort and — in a steadily rising number of cases — a successful return to form and work.

While numerous notable equine surgeons and sports medicine practitioners are to thank for the forward treatment trajectory, four of those include the exceptional minds of Drs. José García- López, Kyla Ortved, Christopher Kawcak and Carter Judy. Their experience runs from academic research to in-the-trenches expertise compiled from decades of work in the surgery suite repairing fractures, elevating technique and, quite literally, writing the book on science-supported rehabilitation.

To set the stage, they explain several fracture types and the nuances involved in diagnosing and treating each one.

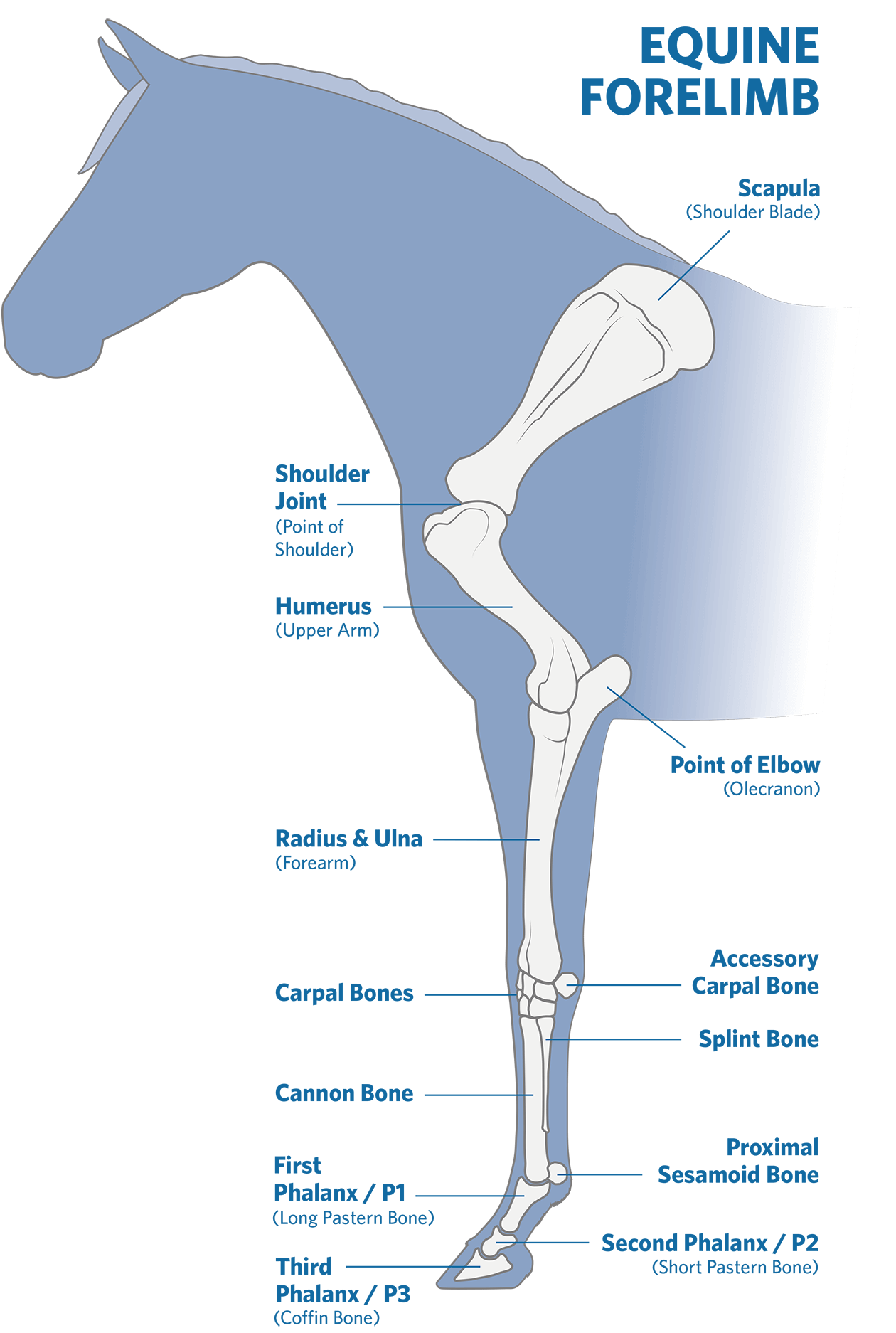

Splint Bone Fractures

While splint bone fractures are one of the most common types of fracture veterinarians see, practitioners will quickly tell you that commonality doesn’t necessarily equate to ease. The splint bones, paired small bones on either side of the cannon bone in the lower leg, are by no means inconsequential and contributes greatly to a horse’s weight-bearing ability. “Most of these fractures are the result of trauma,” explains Dr. Kawcak, a professor of orthopedics in the College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences at Colorado State University and one of a team of researchers working to find ways to prevent and treat catastrophic injuries in equine athletes. “There’s some indication that a percentage of them are fatigue related, but mostly we associate them with a horse being kicked, kicking the stall themselves or perhaps interference from another leg. Things like that.” When the fracture is open, the veterinarian is concerned with wound contamination in addition to the fracture itself. “These are relatively direct to deal with in most instances,” he says. “The bone is either fractured far enough down that we can remove the fractured piece, or it’s high enough up on the splint bone that we can take a small plate or use internal fixation to repair it.” The caveat to this “straight-forward” approach is that, on occasion, the fracture occurs significantly higher up on the bone nearer the joint. “If it’s near the carpal joints of the knee in the front leg or near the tarsal joints of the hock in the hind leg, it does then become more complicated and can cause us to take several factors into consideration. In the case of an open fracture (where a broken bone penetrates the skin), we need to deduce whether the joint is contaminated, then choose the most appropriate repair technique to help stabilize the fracture.” In some splint bone fractures, a surgeon will opt for minimal or surprisingly conservative treatment, while in others, the treating surgeon will elect to execute a more complicated approach involving screws and plates. “Thankfully, except for a small number of cases, splint bone fractures are fairly straightforward to repair,” summarizes Dr. Kawcak, DVM, PhD, DACVS and DACVSMR.

Condylar Fractures

Most commonly seen in racehorses, condylar fractures — a repetitive strain injury that results in a fracture to the cannon bone above the fetlock — are typically due to a combination of bone fatigue and overload. “We don’t see nearly as many of these as we used to,” says Dr. Judy, a board-certified practicing surgeon of more than 25 years and a clinical professor at the UC Davis Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital’s Equine Surgery and Lameness Service. “These fractures are trending downward because of improved footing on the racetrack, as well as other improvements championed by places like Santa Anita,” he adds of the Thoroughbred racetrack in Arcadia, California. “When I think of a condylar fracture, I first consider which leg we’re dealing with, then which side the fracture is on,” he explains. Is the fracture in a front leg or a hind leg, and is it medial (inner side of the limb) versus lateral (outer side of the limb)? “We all prefer the lateral, non-displaced condylar fracture in a young racehorse that takes two screws, then we move on with a lot of success,” he says. However, many of these cases prove to be in a hind leg and are a medial condylar fracture that’s incomplete, non-displaced and spirals up the leg. “These cases can involve a much more complicated repair,” says Dr. Judy. “Arguably, they can also involve a much more complicated anesthetic process and recovery protocol as well.” Years ago, surgeons would operate these cases, place plates knowing full well that a return to work was unlikely at best. “Now, we generally spend a lot of time trying to fix these cases using computed tomography (CT) guidance and with screws alone, then we recover them (bringing them out of anesthesia) in the pool or with a sling. We’ve found that we have better success rates this way,” explains Dr. Judy of the evolution of surgical repair. “We’ve come a long way in treating condylar fractures and have a lot more success now than in the past.”

Olecranon (Elbow) Fractures

The olecranon is the bony portion at the upper end of a horse’s ulna bone at the point of the elbow and plays a key role in maintaining the triceps apparatus and thus a horse’s ability to stabilize its leg while standing. “It’s a long bone that is not directly weight-bearing. It’s attached to the radius, which gives us some biomechanical advantages compared to some of the other long bones in the horse,” says Dr. José García-López, an associate professor of large animal surgery at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine’s New Bolton Center. In some cases these fractures can be non-surgical, but more often surgery is required for an optimal outcome. “This is one of the most common long bone fractures that we see, and it’s not necessarily restricted to one type of athletic work or discipline,” says García-López, VMD, DACVS, DACVSMR. Olecranon fractures can be the result of a kick and can present as an open or closed fracture, with an open fracture posing more risk for complications due to potential wound infection.

Over time, veterinary medicine has standardized a best practices approach to surgical correction. “In most of these cases, we place one, maybe two plates,” explains Dr. García-López. “If there are multiple pieces or if we’re dealing with a 550-600 kilogram (roughly 1,200-1,300 pound) horse with enough fragmentation, we can worry that one plate alone may not do the job. The caudal aspect of the olecranon or the ulna is the tension surface of the bone — it handles the continuous pulling of the triceps. From a biomechanical standpoint, this is why a plate (implant) is typically the strongest choice.” He places significant emphasis on biomechanics and the nuances of each fracture’s configuration to make the best choice for implant number and type. “Which type of bone are we dealing with? Can the repair be placed in the tension surface or the bending surface of the bone?” he asks. “If we’re dealing with a bending surface and we choose to use an implant, we’re going to fatigue that implant just by the nature of how much bending it will experience; that implant will be much more prone to failure. However, by placing an implant in a location that experiences constant tension and pulling — such as the triceps — an implant will become quite strong.” When dealing with the back, or caudal, surface of the bone, a relatively small plate can be the right option for the scenario, rather than a large implant. “If we chose that same plate for a different long bone, it would likely fail, but here the horse would have a good chance,” he says of a generalized prognosis for olecranon fractures. “Overall, we’ve done a pretty good job at getting these horses back to work. These cases can be challenging, and the recovery process as we bring the horse out of anesthesia is critical to avoid failure, but we’ve gotten some good numbers in terms of getting these horses back to performance successfully.”

©PLATINUM PERFORMANCE, INC, ILLUSTRATION BY TOPLINE DESIGN

Tibial, Radial and Humeral Fractures

The bones of the equine proximal limb — the scapula (shoulder blade), humerus, radius, and tibia (hind limb) — are significant weight-bearing structures. When fractured, injuries to these pose several concerns and are first typically classified as incomplete or complete fractures. “If we see an incomplete fracture in a young racehorse, it’s usually associated with stress fractures, especially in the humerus or the tibia,” points out Dr. Kyla Ortved, an associate professor of large animal surgery at New Bolton Center, and a colleague of Dr. García-López at UPenn’s 700-acre campus in Kennett Square. “Those injuries often have an excellent prognosis. If we catch them early, we can pull those horses out of training, rest them and give them appropriate time to heal. We can see great results with that conservative approach.” Contrary to incomplete fractures (a crack or break that doesn’t extend across the entire width of the bone), with a complete fracture, the ends of the affected bones are separated and unstable. “This scenario is a much different picture,” says Dr. Ortved, who joined the large animal surgery faculty at New Bolton Center in 2016 as an equine orthopedic surgeon and was named the Jacques Jenny Endowed Chair of Orthopedic Surgery in 2019. “Unless it’s the rarest of situations, we’re really only talking about fixing these fractures in babies, younger horses, miniature horses, small ponies or very small horses.” Although significant gains have been made in implant technology, the fact remains that with a complete fracture to a proximal bone in an adult horse an implant simply may not withstand the weight-bearing load. In foals and small horses, “We can take a broken tibia, radius or humerus and often put it back together, usually using a minimum of two plates, and through a multi-hour and often very difficult procedure,” she explains. “If we can get the fracture to heal, I would say the prognosis for athleticism in those horses can be very good.”

There are numerous check steps to monitor if the case is progressing or hitting roadblocks in the healing process: performing the surgery; successful recovery from anesthesia; nursing the patient through its first days post-surgery; re-establishing weight bearing as soon as possible; and tracking healing and developing a rehab protocol. “Can we get the fracture to heal, and can the implants hold the leg together until the bone heals? These are two of our first concerns,” she says. “If we accomplish those, then we’re off to a great start, and the horse’s prognosis becomes very positive.” Aside from the challenges, these fractures are prone to infection and pose significant challenges for the opposite (or contralateral) limb. “One of the most important pieces of advice that I was given many years ago is that it’s always important to have the horse evaluated by a surgeon immediately post-injury before rash decisions are made,” Dr. Ortved urges. “Although these cases are challenging, there’s a lot that we can do that many owners may not be aware of — even in severe fracture cases. Don’t panic, have a veterinarian stabilize the leg, then take the time — we’re talking a few more hours or even a day — to have the horse fully evaluated before a final decision is made.”

P2 Fractures

The second phalanx, also known as P2, the middle phalanx or short pastern bone, is one of three phalangeal bones in the horse’s lower leg, located between the long pastern bone (P1) and the distal phalanx (P3). “These are probably the most prolific fractures in our profession,” says Dr. Judy. P2 fractures seem to be non-discriminatory, affecting nearly every breed and discipline, though overrepresented in Western working horses, eventers and jumpers. “The key to these fractures is knowing that they’re almost always articular — meaning that they tend to break into a pastern joint at minimum. We need to establish if the break has gone into the coffin joint as well, which can affect the prognosis and potential for long-term athletic soundness,” he adds. “If the fracture does break into the coffin joint, we can still achieve a positive outcome with proper repair and adequate time given to fuse the pastern joint.” Numerous advancements have changed the game: The widespread use of CT imaging allows surgeons to be well-informed while operating to correct these fractures; improved pastern fusion techniques have drastically improved the prognosis for more severe P2 fractures, providing a fighting chance for horses that previously would have been euthanized; and implant technology means patients recovering from these breaks spend significantly less time in a cast.

These are nuanced cases, but depending on the specifics of each P2 fracture, the horse’s prognosis can be positive, with the potential to return to full athleticism or some level of work.

Other Fractures

While the above offers a dive into some of the most common fracture types, the list includes numerous other fractures, including: the coffin bone (enough to have six defined configurations); the jaw, kicks are common but also open (horseshoe- shaped) gate latches are a common cause when a curious horse reaches over the gate, slips the lower teeth in, then pulls back, trapping the jaw; and the sesamoids, the two small bones positioned at the back of the fetlock joint on each limb (usually related to strain on the suspensory apparatus with accumulated microtrauma). The navicular bone, patella, withers and bones within the carpus (knee) and tarsus (hock) are also relatively common, with vertebral fractures (from neck to tail) being possible as well. Pelvic fractures can vary from life-threatening (picture large blood vessels next to very sharp fracture edges), to career threatening (if the hip joint is involved) to more manageable (the “knocked-down hip” involving only the point of the hip, meaning the weight-bearing structures are unaffected). Rib fractures are somewhat uncommon in adult horses but are a common complication in foals, particularly with aggressively assisted deliveries. Additionally, various chip fractures are relatively common in the fetlocks and knees.

Risk Factors and Preventive Measures

Positron Emission Tomography alone or coupled with Magnetic Resonance Imaging and/or standing computed tomograph have increased veterinarians’ ability to detect lesions even earlier and more precisely.

Positron Emission Tomography alone or coupled with Magnetic Resonance Imaging and/or standing computed tomograph have increased veterinarians’ ability to detect lesions even earlier and more precisely.

With immense progress in diagnostics, treatment and surgical intervention, university teams and private veterinary practitioners have turned their attention to how best to prevent fractures. Several ongoing studies are examining new ways to catch warning signs that stress-related injuries (microfractures) could be looming, as well as to identify potential risk factors that could shed light on why some horses are more susceptible to bone fractures. Advanced diagnostic imaging has improved the ability to detect microinjuries, allowing earlier care intervention. Nuclear scintigraphy, using gamma rays to detect and assess bone and soft tissue abnormalities in horses, was one of the first tools able to show these areas of active injury and remains valuable, particularly for upper limbs. However, Positron Emission Tomography (PET) alone or coupled with Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and/or standing CT have increased veterinarians’ ability to detect lesions even earlier and more precisely. Numerous causative factors have been identified — improper shoeing, chronic or overuse of bisphosphonate drugs, metabolic conditions and insulin dysregulation, stress (or chronic overuse in training) and footing — all precursors of injury, but science is providing more concrete answers as to why.

Research has revealed that one of the largest contributors to equine fractures is in the smallest of details — microfractures. These small insults to the bone accumulate over time to form a “weak link” of sorts, commonly known as stress or fatigue-related fractures. Microfractures are like the perforations between postage stamps, forming with repetitive use and significantly increasing the likelihood of a more catastrophic fracture in that weakened locale. But what causes hairline stress fractures, and how can they be prevented? Up to a point, this is a normal remodeling process of bone breakdown and formation to maintain structural strength and adapt to increased load-bearing. However, if that reparative process is unable to keep up, then the microdamage accumulates along lines of stress, and the risk for complete fracture increases.

One of the largest contributors to equine fractures is in the smallest of details — microfractures. These small insults accumulate over time to form a “weak link,” commonly known as stress or fatigue-related fractures.

One of the largest contributors to equine fractures is in the smallest of details — microfractures. These small insults accumulate over time to form a “weak link,” commonly known as stress or fatigue-related fractures.

Footing has been an intense study area to determine the optimal consistency to allow for high performance levels, while minimizing the risk of soft tissue and bone injuries. The wrong footing can lead to increased loads and microinjury, and can contribute to spontaneous fractures that don’t necessarily start as microfractures. “For example, if you ride on synthetic footing during the cold of a New England winter, that ground can get incredibly hard,” explains Dr. García- López. “We see English sport horses that work on that ground, or even free lunge on it, and they can end up with P1 or P2 fractures due to the concentrated stress resulting from those hard surfaces.”

How equine athletes are trained, as much as the ground they are trained on, can also increase fracture risk. “There’s a lot of effort being placed on injury prevention,” affirms Dr. Kawcak, who leads a research team investigating this subject at Colorado State University’s acclaimed College of Veterinary Medicine. “There are currently six companies out there that have devices or technology that can monitor a horse’s movement and workload, and the American Association of Equine Practitioners (AAEP) is funding efforts for these companies to monitor 100 2-yearold Thoroughbreds to identify horses at risk of injury. That can be done in several different ways, including the use of sensors that measure motion, distance, gait and speed through GPS.” With the use of advanced technology, veterinarians may soon gain a greater insight into how training practices can be optimized to decrease injury risk and, more specifically, fractures. “We know that horses in a higher volume of speed work, or high intensity work, will have a greater instance of condylar and sesamoid fractures,” says Dr. Kawcak. “(Professor emeritus of surgical and radiological sciences) Sue Stover and her group at the University of California at Davis showed that time and time again we can use the information being gathered to better manage these athletes going forward. We also know that horses experiencing these so-called acute fatigue injuries have damage occurring under the surface for weeks and months ahead of the catastrophic injury. The hypothesis is that as the horse starts to develop microdamage before they present with a clinical fracture, they may start changing how they move. These sensors can detect that change in movement.”

Researchers are also looking at physiologic data, including heart rate and heartrate variability, measuring the horse’s response to what’s happening around them during work. “As pain develops, we can start to demonstrate some changes in how that horse reacts to it behaviorally,” Dr. Kawcak explains. “In athletes that are painful or starting to develop pain and stress, their behavior will change.” This is an area where video-based artificial intelligence (AI) is being used to pick up on those cues and gather longitudinal data. “Talk to any good trainer and they’ll probably give you that same information,” laughs Dr. Kawcak with reverence for the trainers who are so often finely attuned to a horse’s behavior. “But this technology allows us to be a bit more objective, and it provides more data to help trainers and veterinarians make decisions going forward.”

Dr. Hannah Carter of Mid-South Equine performs a bone scan.

“It’s important for people to understand that this can be a very emotional time when these injuries happen. There’s a lot going on, but if they can get control of the horse, stabilize that distal limb — even with a splint — and give that horse a chance to at least settle down, then we’ll have time to make an informed decision.”

— Dr. Chris Kawcak, Colorado State University

When a fracture presents, time is the most important initial consideration. Taking time to practice proper field management of the injury by stabilizing the affected limb can then buy additional time for the attending veterinarian to consult with a surgeon, establishing a more accurate prognosis and plan of attack.

When a fracture presents, time is the most important initial consideration. Taking time to practice proper field management of the injury by stabilizing the affected limb can then buy additional time for the attending veterinarian to consult with a surgeon, establishing a more accurate prognosis and plan of attack.

Surgery and Recovery

While researchers give their all to unearth new ways to prevent catastrophic fractures, the fact remains that accidents will continue to occur. When a fracture presents, time is the most important initial consideration. Taking time to practice proper field management of the injury by stabilizing the affected limb can then buy additional time for the attending veterinarian to consult with a surgeon, establishing a more accurate prognosis and plan of attack. “One of the most significant improvements we’ve had in fracture fixation has been the triage care at the front line by the referring veterinarian,” says Dr. Kawcak, offering a surgeon’s perspective. “It’s important for people to understand that this can be a very emotional time when these injuries happen. There’s a lot going on, but if they can get control of the horse, stabilize that distal limb — even with a splint — and give that horse a chance to at least settle down, then we’ll have time to make an informed decision.” He and fellow surgeons often text with veterinarians in the field, reviewing X-rays, photos and specifics gathered right at the horse owner’s property. “As surgeons, we want owners to know that these injuries may look terrible, even to a veterinarian in the field, but these horses can often do very well in the right hands once they reach the surgeon.” In fact, it has become increasingly rare that a horse goes into surgery on the same day the fracture occurs. “Most of the time, we stabilize them, get them calmed down and operate the next day,” he says. This allows for more robust imaging and developing a more thorough treatment plan prior to the surgical team going to work. Additionally, it gives the horse time to learn how to protect the limb, and for the adrenaline to leave its system, making anesthesia and anesthetic recovery safer.

Progress in both implant and plate technology has changed the game (and often, the prognosis) for surgical fracture repair. Moreover, improved anesthesia practices allow horses to experience a smoother recovery as they awaken immediately post-surgically. This time window is critical, as it represents the greatest risk for reinjury. Horses are often in a state of fight or flight as they come out of anesthesia, resulting in explosive and poorly coordinated movements. Veterinary teams know what to expect and use gentle restraints and proper padding to coax the horse upright after regaining consciousness. It’s during this timeframe when warm-water recovery pools are sometimes used to awaken horses in a more tranquil environment, combating the fight or flight reaction and minimizing the forces on the limbs. “We don’t just have to fix the leg,” points our Dr. García- López. “We have to make sure that horse is immediately weight-bearing by aligning the bone, then achieving what’s called absolute stability using as rigid of an implant(s) or fixation as we have.” In humans, a broken leg isn’t expected to immediately bear body weight. In horses, however, that animal must (by necessity) stand up almost immediately after anesthesia. “It’s our challenge to make that patient as comfortable as possible, get them fully weight-bearing on all four limbs and get them eating and moving around to maintain the health of all four feet. All the while, we’re closely monitoring for surgical site infections.”

After surgery, the horse enters the rehab phase with the injury working through the healing phases beneath the skin surface.

After surgery, the horse enters the rehab phase with the injury working through the healing phases beneath the skin surface.

Amie Grohl of Premier Equine puts on Pulsed Electromagnetic Fields (PEMF) Therapy Boot.

Amie Grohl of Premier Equine puts on Pulsed Electromagnetic Fields (PEMF) Therapy Boot.

Rehabilitation

“Fixing” a fracture may seem like the metaphorical finish line of the race, but in reality, it’s more like the start. After surgery, the horse enters the rehab phase with the injury working through the healing phases beneath the skin surface. “Twenty years ago, when we had a horse with a condylar, ulnar or cannon bone fracture, our strategy for rehabilitation was basically the same with every case — one month of stall rest, another month of walking, then to a paddock, then to a larger paddock, then the horse went back to work — if they were able,” remembers Dr. García-López. “There was no variability.” Hindsight is a beautiful thing, and we now know that stall rest is, in most cases, not helping the horse rehabilitate and can typically hinder the healing process, decreasing that horse’s chances for a successful recovery. “We’re doing a much better job now,” he says. “We’re getting horses into a controlled exercise program sooner with more objective or evidence-based protocols. We’re walking them earlier, either on a flat surface or over ground poles, we’re focusing on achieving range of motion and we have access to water treadmills that are deployed if the case specifics are appropriate for it.”

These protocols allow sports medicine and rehabilitation specialist veterinarians to establish benchmarks to better gauge healing progress. “We have to remember that we’re not only dealing with bone and articular cartilage, but often, the horse has sustained a related soft tissue injury as well,” says Dr. García-López. This supports the need for individualized rehab protocols to usher each unique injury along at the proper speed, based on periodic checks, manipulating but not bypassing the vital phases of healing.

“Nutrition is one of the foundations of everything we do. What goes in is what comes out. Proper nutrition, proper weight, proper fitness — they’re all parts of the bigger puzzle, and nutrition provides the building blocks.”

— Dr. Carter Judy, University of California, Davis

The Nutritional Component

Whether the horse has broken a bone or shows signs of microfractures that could lead to future injury, nutritional intervention can play a key role in supporting not just the overall health of the horse, but also the health of the pertinent orthopedic structures and the horse’s ability to heal normally and successfully. “Nutrition is one of the foundations of everything we do. What goes in is what comes out,” Dr. Judy emphasizes. “Proper nutrition, proper weight, proper fitness — they’re all parts of the bigger puzzle, and nutrition provides the building blocks. It provides the macro and micronutrients that need to be available for the healing process to occur. But, more importantly, it needs to be there when those microinjuries occur from a preventive standpoint. If you have a proper nutritional balance from the get-go, and a horse experiences a stress injury, or a microfracture, those nutrients are available for that horse to immediately support healing. You’re in a much better spot at the time of the microfracture than chasing it two, three or even six months later when they have a full-blown fracture.”

Bottom line, it all comes down to the cells.

“We need to not just be looking at the bone and the fracture, and the screws and the plates, but at the horse as a patient, both pre-injury or pre-operatively and in the operative stage” Dr. Ortved says. “How can we prevent these injuries from happening? And if an injury does happen, how can we best support the patient?” In the case of a fracture, the immune system ramps up and this inflammation leads the healing process. Neutrophils, a type of white blood cell that plays a key role in the body’s immune response, immediately come into play, starting an inflammatory cascade, which organizes the cleanup of damaged tissue and stimulates the initial healing phase. Veterinarians aim to manipulate it for a proper balance of bone buildup and breakdown. It’s similar to a hurricane. After the storm, there is debris to clean up. In the case of neutrophils, the equine medical team works to stabilize the immune response and prevent it from running out of control. Excess free radicals, which also play a role in equine fracture recovery, can contribute to the post-storm chaos as well, highlighting the need for antioxidant support to counteract the harmful effects of free radicals and aid in the natural post-injury healing process. “These injuries are very stressful on the body and require a massive metabolic response,” adds Dr. Ortved. “Supporting the horse nutritionally through that process is huge, and it’s something we pay very close attention to. We have a lot of our patients on Platinum Performance’s Healthy Weight oil to try to support them during that post-operative period. Then, moving further out, during rehabilitation when you’re asking these horses to do quite a lot to fully recover, the right supportive nutrition is critically important there too.”

“These horses healing from a fracture need much more than just the building blocks, they need the micronutrients that support cellular transport and aid the natural healing, bone reformation and remodeling processes.”

— Dr. Kyla Ortved, University of Pennsylvania, New Bolton Center

Bone strength is correlated to density up to a point, but other factors contribute to how rigid or bendable bones are. Bone is living connective tissue and is over 30% collagen by volume, with its protein formation being heavily dependent on silica (a compound of silicon and oxygen) and the presence of good quality amino acids. “We’ve used a lot of Platinum Performance ® Equine and Platinum Joint Care + HA, especially when there’s articular components to the injury, says Dr. Judy of how he provides support for the body as a whole and bone health simultaneously, as well as the critical collagen-forming process. “We also add Osteon® for bone support, and I use it for tendon and ligament injuries as well. Where Platinum provides a nice foundation of micronutrients, minerals, omega- 3 fatty acids, amino acids and antioxidants, Osteon® brings in the bioavailable silicon. These horses healing from a fracture need much more than just the building blocks, they need the micronutrients that support cellular transport and aid the natural healing, bone reformation and remodeling processes.”

Additionally, Dr. Judy urges close monitoring of body condition in recovering horses. “We often forget about the overall fitness of the horse,” he says. “As these horses progress through rehabilitation after their injury and repair, they’ll go from being a very fit animal to being a blob, for lack of a better term, and that’s not beneficial to the healing process at all. We’ve got to make sure that we maintain their weight while we get these other components working for us as well. The whole body needs to be in balance for these animals to work and function properly, let alone heal — that includes muscles, nerves, soft tissue and gastrointestinal health. Nutrition is foundational, it’s one of the things at the bottom of the pyramid in terms of preventing these stress injuries, along with generalized fitness, proper training and things like that.”

“Even if the fracture looks hopeless, it’s worth consulting with a surgeon that has experience with fractures to be sure. We can very often save the horse these days.”

— Dr. José García-López, University of Pennsylvania, New Bolton Center

The Journey Continues

Research marches on in this area, focused on how best to prevent, treat, operate, heal and rehab fractures. Progress thus far has been spurred by the curious veterinary minds at work in both academic institutions and daily practice. Research and clinical learning have collided to deliver better-than-ever prognoses for horses that have sustained a fracture and those that — thanks to more predictive, preventive technology — have been identified as high risk for developing a future fracture. Veterinarians — together with owners, trainers and riders — are working to maintain healthy and thriving equine athletes with strong structures, ideal metabolic function and optimal longevity.

Horses are unpredictable and when a fracture occurs, improving protocols are giving the horse the best chance at a positive outcome, even before they’re on the operating table. “One of the challenges historically — and we still experience this — is that a horse will be euthanized before the owner or attending veterinarian consults with a surgeon,” says Dr. García- López. “Even if the fracture looks hopeless, it’s worth consulting with a surgeon that has experience with fractures to be sure. We can very often save the horse these days.”

From nutritional intervention to improvements in imaging, surgical techniques, implants, wound care and rehabilitation practices — fracture patients have the best chance at not just surviving a broken bone but recovering with the hope of returning to some level of work and, in more cases than ever, going back to full performance. “It’s a challenge, and you’ve got to be ready to pivot. But, it’s a challenge we’re up for,” says Dr. Kawcak.

Osteon® Offers Bone & Soft Tissue Support

Supplementing with a natural, highly bioavailable form of silicon like the zeolite found in Osteon® can provide effective support for bone strength and development. The trace element is also important to the formation of articular cartilage and connective tissues. From bones to connective tissues, silicon plays a key role in maintaining a healthy body structure.

“I am using Osteon® to help my mare recover from a soft tissue injury. This is the first time she has been sound since her injury two years ago. Osteon® has supported stronger connections in her soft tissue and is helping her recover.”

— Katie K.

Subscribe to the Platinum Podcast

Fractures

A dynamic collective of expert equine veterinarians dive into the subject of orthopedic fractures, discussing the evolution of preventive, surgical and rehabilitation protocols and how equine patients — now more than ever — have the most advantageous chance at survival and recovery.

Listen Now